Meeting with Peter Tóth, Curator of Greek Manuscripts, Bodleian Library, Oxford, Tuesday 14th May, 1.oopm

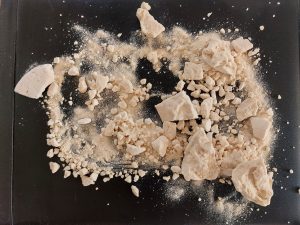

The unglazed side of the pottery was used to write upon. After the second use of a shard, it would be thrown away thus large numbers of this kind of palimpsest can be found on ancient rubbish tips.

Greek schoolchildren would use them for their homework. An entire homily (sermon) was written on a shard. Homer used them to write on.

Palimpsests viewed and discussed at our meeting:

Wax ‘slate’ palimpsests were used with a stylus to write upon. Peter used a modern remake of one to demonstrate how it would have been used, the flattened end would have been heated and used to smooth over the wax to erase previous marks. This object, two wooden blocks, tied together at the spine with leather thongs clearly show how the book form derived from them. Tablets such as these would have been widely used within administrative operations. Sometimes people would press so hard into the wax that they would make impressions in the wood underneath, which can also be interpreted and read.

The word ‘palimpsest’ is from the Greek meaning ‘scraping again’. Peter contends that if you cannot see the undertext you would not call a document a ‘palimpsest’. It is the undertext that he, personally, is most interested in and part of his work is to decipher what the undertext says. Peter explained the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the Pharoahs and from that time on papyrus was used. A shift was also made from hieroglyphs to demotic language. Hieroglyphs were sacred, were meant to be forever and represented the language of the gods. Demotic language was cursive, much more hurriedly written and became widely used in literature. An example is the Ancient Egyptian owl, which was a very beautiful drawing of an owl. With the shift to cursive it was represented by a curved line. Demotic, cursive language could be understood by everybody. Alexander the Great’s conquering of Egypt brought with it the widespread use of Greek as the official language of administration. Greek papyruses stem from the seventh century but from the fifth century onwards Latin was growing as the dominant language under Roman rule.

In recent years advances in visual imaging techniques are making possible readings of palimpsested undertexts. An example of a project seeking to read, interpret and understand palimpsests is the Sinai Palimpsests Project:

https://sinai.library.ucla.edu/

Bel and the dragon; Grammatical text; Homily, 3rd century – 5th century, Egyptian, Greek and Latin, parchment

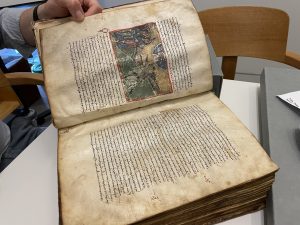

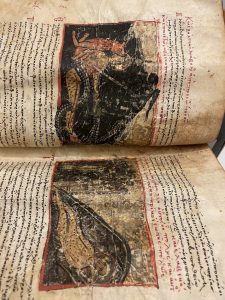

12th – 13th century parchment codex telling the story of Job with illustrations

The sons of God present themselves before God. Satan. (Job 1, 6-7).

Job covered with boils. (Job 2, 7)

Questions I prepared to put to Peter. Some of these were answered by Peter in conversation as above. The remaining ones I shall put to him via email now.

- Is there a correct definition of ‘palimpsest’ or can the term be used as loosely as it is?

- What differentiates palimpsests of images from those of texts?

- What is the type and range of materials and media used for palimpsests?

- Are there examples of palimpsests where a writer was trying to perfect or improve upon their text by writing over it?

- Are you aware of other artists who make work as palimpsests?

- What do you like or enjoy about palimpsests?

- What is their principle difficulty?

- What makes a palimpsest interesting to you?

- What would be your question to ask of or about a palimpsest?

- What was the third example of a palimpsest you were going to show me but which we ran out of time to view?

Answers to my questions sent to me by email by Peter Toth:

- What differentiates palimpsests of images from those of texts?

Nothing really, the idea is the same, to erase something to be overwritten by something else. Maybe the nuance is that images are often erased with some intention on top of the practical consideration of getting a cheap new page (which is often the case with texts). There is often a specific reason why they decide to get rid off the original image: we saw that representations of the devil are often scratched out (fear/hate against seeing him), images of unwanted people, saints disliked later (Beckett was often erased from MSS during the reign of Henry VIII) etc.

- Are there examples of palimpsests where a writer was trying to perfect or improve upon their text by writing over it?

I am sure they are but it is very rare with a whole page or sheet. What usually happens is that they erase a word with a typo or mistake and write the correct one instead, on top. But I haven’t seen this in a unit more than a line but that is already very rare. In case a larger amount of text was thought to be superfluous they simply cross it and start again. See Thomas Aquinas’s handwriting here https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.9851/0051

- Are you aware of other artists who make work as palimpsests?

I am not the right person to ask about this, I am not very familiar with contemporary art but I am sure there are others approaching this theme from various angles. Gerard Genette would be important to refer to in this context…

- What would be your question to ask of or about a palimpsest?

I am always selfish in this situation. I want to know what the undertext exactly is, what is its date and relationship to other manuscripts of the same text to assess the value and position of the earlier undertext. It is only after this, that I would try to find out what the undertext has to do with the upper text and if there was any specific reason why it was decided to be erased.

- What was the third example of a palimpsest you were going to show me but which we ran out of time to view?

I think it was a Latin palimpsest which we could not see Ms. Laud. Misc. 391, f. 57-64 but that is fully digitised so easy to compensate for see it here https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/c2ed1c10-4520-4b4f-b0e2-8ba6e0720890/surfaces/44aa2b54-94b9-4d31-94b5-db4ffc93ac6a/ By all means do take a look at the brilliant project at the Sinai Monastery digitising all their palimpsests and making major discoveries. It is all online at https://sinai.library.ucla.edu/ you need to register but it is easy and free.