A piece comes to me very early on. Bearing in mind the work should be off the floor and the walls cannot be drilled into. The work must hang to be in keeping with the conditions of the space it is shown in. Or be integrated in other ways into the life of the space, as serviettes, or cushions or other ephemera. But the work should endure for the life of the exhibition, be in keeping with the life of the Byre but not be too self-effacing. How work is and what it becomes has a lot to do with how one is in social situations, though the work can be more visible, more daring and make more of a statement than my own physical presence might like to be. The work is not me, it has, or should have, a life of its own.

I say to Jan in an email: “I am someone who works with given conditions and contexts. So I have already taken all the points you raise into account in my design of the artwork and am happy with the situation. You gave some very useful and comprehensive information when Elise first discussed the project with you, which she passed on to me. I am more than happy with the space and would like to build something of the specific history of the Byre Theatre into the new work, using the digital archive of images from its history that now exists. I like that the audiences won’t be primarily art audiences but that the work will be seen by anyone visiting the theatre, the cafe, using the social spaces. This is good for arguing the case for impact as well in terms of broadening the reach of the work.

I have studied the images of the available spaces you sent through and think I understand the hanging system in place and will work with that. I also appreciate the age advisory aspects and have made many public art commissions in museums and public spaces so am used to working to the conventions around this.

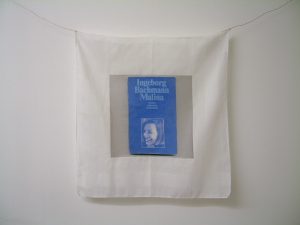

At the moment I am envisaging a diaphanous wall hanging (possibly on repurposed silk) of digital photographic images of familiar objects, from Ernaux’s writings, from my life and from the Byre archive. Things like a kettle, a table, a handbag, etc, ordinary everyday objects that people can relate to. It would be very lightweight, fairly indestructible and if it were to hang above the staircase on the large wall it would be out of the reach of anybody of any age or height.” (23 January 2024 email to Jan McTaggart, Deputy Director, Head of Programme and Marketing, Byre Theatre)

Summary of ideas so far compiled Tuesday 20 February

Silk wall hanging – objects overlaid

Rough draft for Christmas card Dec 2022 (unrealised)

Outlines from Byre Storeroom photograph inventoried above with selection as ‘archetypal’ images compiled from Ernaux, Byre, Diab. Composite.

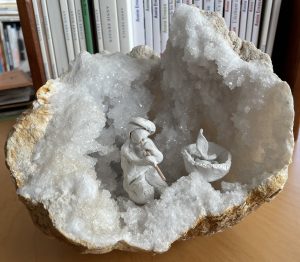

These, or other, objects made in miniature from clay, fashioned by hand, as ‘props’, arranged in different combinations, photographed.

___

First exhibited work, ‘Must Sort Out That Drawer One Day’, 1991

Fantasy of order/organisation as understanding, overview, or comprehension of life.

Whereas life consists in overlap, misplacements, random configurations, disorder.

Front

Reverse

This piece consists of three panels with all materials taken from the odds and ends drawer at my Mum’s house, the house I mainly grew up in, in North London. The three panels were made only using these materials, which were sorted into their kind:

Wood: a wooden ruler, buttons, old pencils, worn down, nuts in their shells, some almonds,

Wax: from candle stubs and wax crayons

Metal: cutlery, scissors, hairclips, badges

Fabric: linen napkins, baize felt, remnants of dress-making fabrics

Paper: family photographs, Church collection envelopes, dress-making patterns, greetings cards, hospital appointment notices, price labels, recipes, shopping coupons, dishwasher tablet wrappers (foil), restaurant takeaway menues, confetti box

Combinations were made of materials in order to form panels:

Wood set into wax

Metal flattened at a Blacksmith’s forge and stuck together (rather unsatisfactorily) with glue

Paper cut into hexagonal templates for patchwork, as selected images and text set into reverse side of the fabric patches

‘Palimpself’ bringing me round full circle to where I started with this piece which looked to the future, to an imagined point where it would all make sense to me and meaning would be revealed. As I said, a fantasy.

Relates now to the ‘Dooferooney Jar’, being a large glass jar that originally contained preserved peaches, filled with small objects I couldn’t quite decide to get rid of when we cleared the parental home after the death of my Mother. For some time this jar has sat, unopened and unsorted under a glass dome (the type for museological display) in my study, gathering dust. The fantasy, to open the jar, take out each ‘thing’ and find it to be of indescribable charm and meaning. The fear, the objects would have no such resonance and be disappointing. So, far better to defer the pleasure and let the assortment of objects ‘brew’.

Dooferooney Jar, photographed Wednesday 21 February 2024 unposed as is in study, with dust, photographs of parents behind. Objects contained behind two layers of glass, with reflections.

‘Dooferooney’ from ‘to do for’ as in a reason to keep something rather than throw it away. It might ‘do for’ this or that at some future point.

Photographed previously 10 November 2022 in studio:

These two taken as seen in the viewfinder of my Dad’s old medium format camera, (uncleaned since he would have last used it in the 1950s or 60s)

__

Shapes laser-cut as frames for small scenes painted on silks as envisaged from Ernaux descriptions. Two cut-outs the same sandwiched together with the image on fine fabric between.

__

French ex-military ‘silk’ parachute. (Small print shows it to be silky fabric, not necessarily silk).

Jellyfish,

Imagine suspended above staircase in Byre foyer.

Keep coming back to as source of some thread of thinking, not yet understood.

Research significance of silk: recycled parachutes, has fallen through the sky, poetic, non-stretchy, lightweight yet very strong, luxury references (Blackhurst article).

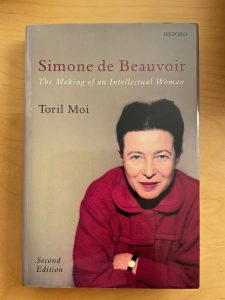

Other currently relevant visual source materials:

Deconstructed bottle, street, 18 February 2024

Bled – Offspring, disturbing crop of image, ‘Happening’

Tate Britain, ‘Women in Revolt, Valentine’s Day with Kath, screen at entrance, feminist badges, find out who printed screen etc., not great sharpness but like its translucence.

Charity shop window, 13 February, 2024, things hanging, labels, always stop to look, cutlery

Wall ghost. Black damp mould on exterior of house in Portslade. Interesting as presence. 4 February 2024

__

Next Steps:

Recap and write up all readings, notes and annotations of Ernaux so far about materials, objects, etc.,

Read: L’Usage de la Photo

And other texts outstanding

Refs given to me by Elise not yet read – recover references already given in emails, write out and summarise

Order library books

Make:

- Object arrangements on iPad in layers from Byre and other photographs

- Miniatures from objects

- Outlines: layers as frames

- Experiment with bright-coloured gels for objects

Research stained-glass. A friend has offered to teach me stained glass, not as intention for final work but as experiment for processes and discover relevance.

Revisit and take photographs in St Margaret’s Church, Ditchling, where we were yesterday (20 Feb) for Simon’s funeral. Take stills of trees blowing outside nave window disrupted by stained glass panes. Lamb of God cut up like ‘cuts of meat’ charts. Juxtapose these images.

Research processes for printing on silk and silk-like fabrics.

Plan research trip to Byre Theatre and to meet Elise and Jan, for a point not too soon but early enough for understanding of site to be gained.

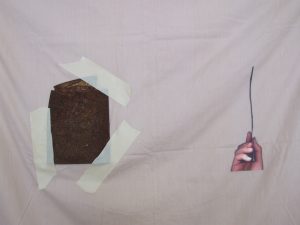

And this, object, traffic-flattened tin can, attached to the lining of an old curtain (from my Gateshead Granny’s house) next to a cut out of a printed image of my hand holding the tin, photographed from the side to show its flatness. Three-dimensionality, into two-dimensionality back into three-dimensional materiality.

And this, object, traffic-flattened tin can, attached to the lining of an old curtain (from my Gateshead Granny’s house) next to a cut out of a printed image of my hand holding the tin, photographed from the side to show its flatness. Three-dimensionality, into two-dimensionality back into three-dimensional materiality.