It may be that I am getting somewhere near to where I need to find myself to conceptualise and realise this piece. I seem always to have thought of the work for this commission as ‘a piece’ rather than several pieces, though that is possibly a bit restrictive, and I will, as always, allow space for the unexpected to take place and then decide what to show after the work is made. I think that’s typical of the way I work as well, to have something ‘decided upon’ to fall back on if all else fails, to know that I will ‘come up with the goods’, a kind of safety net.

Yesterday in my studio I got my hands on some clay at last. I say “at last” because I have been prevaricating for a couple of weeks about doing so. In those two weeks I have concerned myself with other, necessary matters, booking my ticket to St Andrews to visit The Byre to experience and measure up the display spaces and possibilities, researching and buying a laser measure, continuing to write up my annotations from those Ernaux texts I have read so far and adding them to the blog and so on.

‘Chair’ approx 10cm tall, in French ‘chair’ means ‘flesh’

I was smiling to myself in my studio because of the way the day proceeded. I had gone there determined to have made something out of clay by the time I left at the end of the day. I set everything up on my desk, had found my ceramic tools and arranged those things around me that I needed to work with but still I was holding off getting on with it. First, I decided, I needed a shortlist of objects to work with so I spent at least half of the time I was there going through my document of excerpted quotes from Ernaux and lifting out of them the concrete nouns which I put into a long-list in another document:

Objects – an incomplete list of nouns (concrete or as concrete as they can be, in any case, not proper or abstract nouns) appearing in Ernaux texts:

a brand-new smock to start the term

my beautiful missal

suspect nightgown

some foreign object

that room

those curtains

the bed

Ikea furniture

a probe

a small table with a formica top pushed up against a wall

an enamel basin with a probe glowing on the surface

a hairbrush

a lipstick

the bathrobe

a bundle of rags

a glass from which he had drunk.

this photo

St Anthony’s tomb

a handkerchief

a folded slip of paper bearing their prayers

fur coats

evening dresses

villas by the sea

toiletry bag

bedside table

a drawer

a manicure set made of black patent leather

imaginary objects

her shelves

her belongings

the little chimney sweep above her bed

the cake

golden dishes

money

a TV screen

a book

a newspaper

a cardboard bustle

heads

animals

yo-yo

wine

cider

wedding photograph

the half-veil hugging her forehead

the camera

small moustache

starched white collar

aperitifs

tinned delicacies

the funfair

huge, frightening merry-go-rounds

decorations

a few framed photographs

some table-mats

the mantelpiece

large china bust of a child which the furniture man had given away as a free gift when they bought the corner settee

the jacket of her two-piece suit over her shopkeeper’s coat and had knotted a scarf around her head

the bedside lamp

lamp was in the shape of a ball resting on a marble base with a brass rabbit sitting upright, its front paws sticking out at its sides

a stained pair of underwear

bottles of sparkling wine, sponge fingers and Chamonix orange biscuits

corkscrew curls on her forehead are produced by rollers she pins into her hair at night

her spectacles with their jam-jar lenses

a navy blue car coat

beige wool loden

a pencil skirt in thick tweed

a striped sailor jersey

a grey suitcase

a blue and white plastic bucket bag

a great red staircase like the one in the painting by Chaim Soutine

a red hardcover diary from 1958

an image of a room with an image of a dress and a tube of red Émail Diamant toothpaste (memory is a lunatic props-mistress), reducing me to the state of a spellbound viewer of a film utterly devoid of meaning.

her ring with a blue stone and the letters stamped FM

a little diary from 1963

stones

a kind of tableau appears before me – a castle and its grounds, completely overrun by the vague forms of children, dressed in blue from head to toe

mocha cream cakes

coffee éclairs

Equanil tablets

a biscuit tin

a jar of sweets

key

the chest of drawers with the looking-glass above

a record of Strauss waltzes

the wide-scale clearance of a memory warehouse sealed for decades

new objects

display stand for chocolate bars and rolls of Smarties

my blue and white bag

trinkets from the shelves at Woolworth’s – lipstick, nail care and sewing supplies

food

blood

the boundaries of the body

the bar of soap

words written in red toothpaste on the mirror

the jukebox that played Apache in the coffee shop of Tally Ho Corner

the name Paul Anka deeply engraved on a desk at the lycée

45 rpm of Only You

Then I wanted to put some music on to play and had brought two Kraftwerk CDs with me that I bought last time I was in Oxford. I took one out to put on to play on my computer, but the laptop is less than a year old and doesn’t have a CD drive, which I’d forgotten when I packed my two big bags to go to the studio that morning. I actually have an external CD drive but had forgotten to take it with me. Then I remembered that I had a CD Walkman somewhere and after a search found two in a box of electrical odds and ends. However, neither, being Walkmen, had the facility to play music out loud and both had old-fashioned earplug jack sockets. Did I have any earplugs on a wire I could plug into one of these devices? No, only airpods, working from Bluetooth, a technology of today and way ahead of these two old devices. For one of the Walkmen I could at least find the mains lead and I just about got it going but – no sound.

Delay delay delay. My first ‘boyfriend’ was German. He had joined in with our class mid-year when I was at Junior School, when I was ten. He didn’t speak any English at that time and sat at the table I was on. He had fine features, blonde hair, a very sweet face and smile and came to us with a tragic story. It was said his father had been a helicopter pilot and was killed in an accident and his mother had remarried an Englishman and so they had come to live in England. I was smitten. We taught him English, all the ‘rude’ words at first of course, and delighted in hearing him repeat them. I’d love to know now the list of words we thought of as rude at that age. When we left Junior School he signed my autograph book and I used to pore over his signature and imagine romantic adventures. In fact he didn’t sign it but did something I thought quite original and inventive. He folded over the corner of a page and wrote on it: ‘For a very dirty girl’ and underneath, when you lifted the flap, was an oval shape drawn with ‘SOAP’ written on it. Thinking about it now, I don’t know if he was referring to my expert knowledge of rude words for my age or whether he meant that I smelled. At the time I only ever had the second interpretation and was amused by it. I’ve still got the autograph book somewhere and could probably locate it for you and show you the page. It has a purple, slightly padded cover with a line of the outlines of stars in white on it is A6, landscape format, with pink pages.

After Junior School I went off to the Girls’ Grammar School in Barnet and he to the Boys’ and I didn’t see him again until the Sixth Form when a newly introduced scheme to merge, and hence widen the choice, for girls’ and boys’ ‘A’ Level provision by joining the two sixth forms brought us together again in our joint ‘A’ Level German set. I had a terrible and traumatic start to my ‘A’ Levels, it not having been possible on the timetable to take four subjects and thus do Languages as well as Art and English Literature. When the timetable was given to me Art clashed with German on every day of the week and when I went to my teachers for advice they told me that they considered me capable of just choosing which of the two lessons I felt like going to on any one day. When I think about that now, it’s extraordinary; they must have thought that I would be able to pick enough up along the way during the two years to complete and pass the exams even though I would have attended only half of each of the two subjects. Or else they assumed, which I think is more likely, that I could just do Art on the side, not treating it as a proper subject requiring adequate study time and engagement. Art was considered a non-academic and therefore, less ‘serious’ subject, a kind of anti-intellectualism when it comes to art which still pervades and which has set up strange oppositions in myself ever since.

I started off the courses intending to straddle German and Art as they suggested but when I saw G. in my first German class, the angel of my childhood crush, that was it, I decided on the spot, art went out the window and I committed myself fully to German. He asked me out within the week, we went to see a film at the Odeon together, snogged a lot and spent hours sitting on his bed holding hands listening to Kraftwerk . . . ‘Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn.’

*

For some time I have been aiming for a list of objects lifted from the texts that I could make in clay for photographing and putting on the screen. I am wondering whether from now on to refer to the fabric onto which the images will be printed as ‘the screen’ because I have been finding using different terms for it slightly confusing. This is the first time, in writing this, that it occurs to me that that is what it should be called. I like thinking of it and calling it ‘the screen’ because that makes of the work a kind of film still, which is close to what I envisage it as. I want it to be a moment captured in time and ‘screen’ refers to the fabric onto which a film is projected as well as a sheet of fabric or a stand whose purpose it is to obscure something from view: going behind a screen to undress on a visit to the doctor, a flexibly positionable, Japanese, paper screen, for instance, to create a temporary wall in a room, dividing and designating its different uses.

This wouldn’t be the first time I have made a screen. In 2003 I took part in an exhibition ‘After Caro’ commissioned by the Hampshire Sculpture Trust of work made by a younger generation of sculptors, to be shown alongside a major retrospective exhibition of the works of the British sculptor Anthony Caro in Lewes, a town inland from and east of Brighton. As part of this we were invited to visit Caro at his London studio, in Camden Town. We were shown round his workshops and then given tea around a large table and introduced individually to him. I was introduced to him as a ‘video artist’, which I’m not, to which he replied ‘video can’t be art’, which it can. But then he added a rejoinder along the lines of but what do I know, I’m in my eighties now and you have to remember that Monet in the 1920s and 30s found himself still painting in the middle of surrealism.

Sir Anthony Caro and Ann Elliot, independent curator of Caro’s retrospective exhibition in Lewes, 2003

I do not think of or call myself a video artist but I did use video in one of the pieces, which I made for that show and it was called ‘Projection Onto Objects’, a descriptive title because I did not really want this work to be ‘about’ anything other than what it was. My idea was to make a three dimensional screen onto which I would project a simple animation of shapes which, in being played over the surface of this ‘lumpy’ screen would be distorted. So, it was about the interaction of the screen and the light projected onto it, making of the screen not just a passive receptacle for the image, but a surface that is in dialogue with whatever is projected onto it.

The finished work ‘Projection Onto Objects’ can be viewed on my website:

https://www.susandiab.com/?page_id=167

A red dot appears on the centre of the screen which grows to fill most of the screen and then shrinks back again followed by a black line, which scans down the screen from the top to the bottom. As they move over the surface of the screen, the form of these shapes is changed and distorted by the three dimensionality of the objects which protrude from the screen. The screen itself was made from objects I found on the street stuck to a backing board and painted white, like a conventional screen. This random assortment of objects included: an empty cornflakes packet, a rather elaborate ceiling light-fitting including the chain from which it would have hung, a holdall-type bag with a broken zip, a plastic shower mat.

I’ve still got the screen, it sits propped up against the wall of my studio getting gradually ever more delapidated:

It’s aged since 2003 when it was first shown. Some items have come unstuck from the back board, others fallen off but I’ve kept all the bits and could remake it good as new in very little time, a coat of fresh white paint and it would be revived. I’m wondering now why I treat it as I do, have never covered it, wrapped it carefully for storage as I have most other items relating to works I have made? There will be a reason.

Things remain stubbornly from the past, concrete ghosts of our previous relationships and markers of our losses. I am lucky and cursed to be the offspring of parents with hoarding tendencies. I know and understand their need to hold onto stuff and to cart it around with them from one place lived to another, often at great expense and effort. The story about them eventually leaving India to come and live in England at the end of the nineteen sixties, when I was three and a half, was that in addition to having furniture shipped over, they had with them on our trip home, not only their three young daughters but 21 pieces of hand luggage, which they moved from train, to boat to train. How on earth they managed this I have no idea, except that in those days porters were to hand in stations to help with moving luggage for a gratuity. In the photos of our stop overs in Venice and other places, there are no visible signs of the hassle, instead Mum looks remarkably cool in her white cardigan, neat dresses and shades, posing for Dad’s camera eye, several arms, Indian goddess-like, holding on to various little girls’ hands, their coats, her own handbag and sometimes carrying me on one of her hips, always smiling at the lens, as required.

There are advantages to their reluctance to let go of their possessions, to reduce their amount and lighten the load. Going through documents as part of the process of sorting out their house before it was sold, after Mum’s death, I found a letter she had written to my Dad from the nursing home in Gosforth the day after my birth. Dad had stayed behind in India. She describes their new daughter to my Dad with lots of affection in her words and gives a detailed account of the birth itself, which, thankfully, was quick and straightforward. I learn that I “came kicking into the world” and that my sister L., only four herself at the time, was going to visit the next day and had said she would give me her littlest dolly as a present. Needless to say that letter is something I cherish. Written on air mail paper, it was posted to India, received by my Dad, kept, brought back from India to Gateshead, then moved with them each time from Hedley Street to Devon Gardens, to Saltford, to Barnet. I keep it safely and take it out each year on my birthday and read it out loud to myself to hear her words and reach for re-feeling our closest of ties. I sometimes also read it through on the anniversary of her death, May 13, to console myself.

Re-membering

Around 2002 I was artist in residence at Hastings Museum and Art Gallery and Hastings College. The aim of this residency across two institutions was to encourage more students from the college to visit and make use of the museum. The college had a high proportion of art students taking their various art courses and degree courses and the museum is a fabulous resource comprising local history, a fine ceramics collection, some unique aspects such as the Grey Owl display and archive. Grey Owl was the alias of Hastings-born Archibald Stansfeld Belaney, who had lived with and ‘become’ (in the sense of claiming to be) a member of the native American Apache community in the first part of the twentieth century.

Perhaps the most impressive feature of the museum is the Brassey Collection of artefacts collected from around the world by the Brassey family, English engineers who made their money in the railways, bought a ship, The Sunbeam and sailed around the world, visiting places and bringing home souvenirs. These various items are housed in the impressive ‘Durbar Hall’, an annexe to the museum, built onto its northern side, a carved wooden display on two floors with an upper walk around gallery, which was originally manufactured for the Great Exhibition of 1851 and then reinstalled onto the museum to house the Brassey Collection. My idea for the residency was to site myself in the college and invite students to visit the museum on my behalf, look around the displays, choose an object and then come back to see me in the museum to describe their chosen object from memory, which I then drew unseen based entirely on how they described it. After some weeks, I then visited the museum myself, searched for the objects they had selected and photographed them making an animation in which the photos emerge from the drawings by way of comparison.

From top, three stages of the animation, ‘Re-membering’ projected into a display case in the Durbar Hall, Hastings Museum 2003

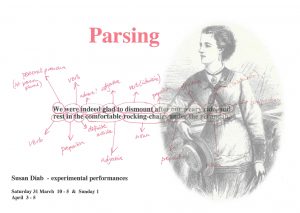

I also made a performance called ‘Parsing’. Wearing a crinoline cage on castor wheels fashioned out of bent steel tubing with an upright six foot pole arising out of the back of its waistband topped with a bright spotlight shining down onto my head, I perambulated around the ground floor of the Durbar Hall reading aloud from Lady Brassey’s account of the family travels ‘A Voyage On The Sunbeam’. That is, I read the text giving voice only to the concrete nouns, in order to allow only the things they noticed, were gifted, bought or took from the places they visited. I called this ‘Parsing’ to create a connection between the actual artefacts on show and housed archivally in the Durbar Hall and how objects are lodged in speech and writing and can be revealed by a focus upon them. The performance was open to the public, one loyal friend came all the way from Brighton to see it and I possess only one out of focus photograph as documentation that it even happened. I have searched my entire office but can’t lay my hands on this photo.

Instead here are: a poster for the performance, a digital mock-up of the planned arrangement of spotlight atop a 6′ pole attached to a steel crinoline.

[Notes to follow:

Things: not being able to get rid of them, choking up space, as friends, a being loaded with meaning. Charged objects.

Having worked out that the fabric is a ‘screen’ I know now that its purpose is to show arrested movement.

Experiment with photographing objects mid fall.

Good to be able to tie the work in with previous investigations]